In part 1 of his CX series, guest blogger Frank Borovsky, vice president of industry sales at Salesforce, explores why not all customers are created equal, and how to determine customer value and execute accordingly. Read part 2 here.

Not All Customers Are Created Equal

For many companies, this is the beginning of strategic planning season. The recurring theme I’ve heard most during the last decade is “make it easier to do business.” When tackling this, many Customer Experience (CX) practitioners start their efforts with the customer journey or with metrics associated with customer support calls or case resolution.

Certainly, those are important elements to consider and should be simultaneously addressed based upon burning business imperatives, but they can potentially become distractions from the most important: current and future customer value.

Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) attempts to quantify in dollars the value of a customer relationship to your company over a period of time. Not all customers are created equal. But without this analysis, all customers, regardless of size or value, are likely to be treated the same. This is a strategic mistake, and any work you do without CLV as your compass may be misleading. Your journey maps or KPIs or case management efforts will be based upon the average performance of the masses rather than the customers you should be caring about most.

How Much is a Customer Worth?

In the make-to-stock or configure-to-quote manufacturing world, CLV starts with the fully burdened product margin based upon the specific final price actually paid by the customer, plus as many allocations associated with “cost to serve” and “cost to sell” as can be measured. If you have engineered-to-order products or projects, then all associated development, engineering and project management costs need to be included as well.

Your construct is attempting to create a current cumulative net present value, similar to an income statement, but with a longer time horizon.

Cost to serve might include such items as order processing, which can vary considerably depending upon mode (e.g. Electronic Data Interchange or eCommerce, which might be pennies per transaction versus a phone call, which could be tens of dollars or more.) It also would include time and effort associated with disputes, returns and warranty claims.

Cost of sale would include acquisition costs and a fair share of a salesperson’s (and their boss’s) salary and bonus as well as any commissions associated with the relationship or transactions. Because these costs differ from one customer to another, it is important that the allocations not be peanut butter spread, but specific to the number and type of transactions directly associated with each customer.

I’m happy to debate the level of detail that one should take in devising the calculations - and you will certainly find diminishing returns at certain levels - but the idea is to address the core areas that distinguish one customer’s contributions and costs from the next.

Evaluating Your Customers like Employees

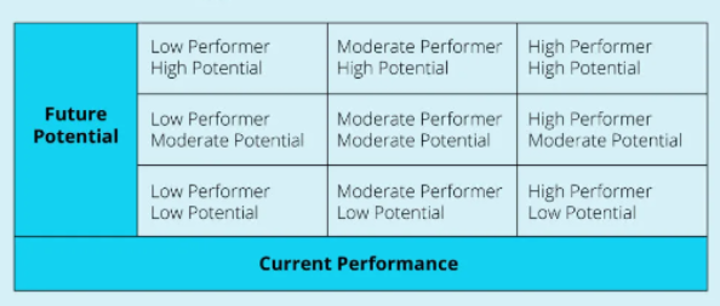

Do all your employees perform equally? Do they all have the same potential to perform in the future? This famous 9-box grid, created by McKinsey in 1970, was originally used by GE to identify key investments and to compare various business units. The same process later evolved into a widely used HR tool to assess the performance and potential of employees within the company.

Initially lauded, and still widely used by many Fortune 1000 companies as part of their talent and succession management process, the grid or matrix has been criticized for force fitting employees into highly debatable categories based upon subjective criteria.

While the controversy over using the 9-blocker for employees may be appropriate, why not consider its merits using controvertible objective criteria to identify and assess the past, current and future performance of your customer base?

There are at least two approaches to follow when applying the 9-block concept to customers. One is product profitability versus cost to serve/sell. Another is total current/recent value versus potential. The former simply looks at current state. The latter requires both subjective and objective criteria to assess future performance. (Enjoy the worthwhile and fun debates that ensue as you attempt to determine what factors are most likely to accurately predict).

Once developed, using the concepts of CLV (profitability) and cost to serve, the CX team should be looking at the customers who fall into the low profit/high cost category, and investigating the root causes.

What makes them less profitable than the others? Are the costs to acquire or costs to serve them too high, or are our prices too low? What are their future prospects? What data do we have that tells us that they will grow over time, or what behaviors can we change to bring these low performers up to the level of those with high performance and future potential?

These are the vital questions CX needs to answer.

How CLV (or lack thereof) Impacts Incentive Programs

At one company I know, a distributor was emailed a spreadsheet quarterly showing total sales year-to-date. Not only was the spreadsheet out-of-date, but because it was sent so late after the quarter, it failed to provide the necessary incentive to maintain current status much less aspire to the next tier. In this case, the distributor told me that had it known earlier in the year, it would have changed its buying patterns to meet the requirements of the loyalty program. So, the company missed out on revenue and the distributor was disappointed by its customer experience.

Compare that situation to what you and I have come to expect from the airlines. When planning a vacation, we can look up our latest points and determine what the flight will contribute to our existing tier and how many points it will take to achieve the next. We get texts and emails reminding us of our status at important intervals.

Why should any other customer experience, whether B2C or B2B, be any different? That’s why the company mentioned above developed a distributor portal to promote eCommerce and self-service. Front and center of the splash page was the current loyalty status and the associated benefits for the current tier and additional benefits for reaching the next tier. Whether you call it behavior modification strategy or gamification, that is what a loyalty program is meant to do.

Bottom line

CLV ultimately helps you make more fruitful decisions on where to invest precious time and resources in your customer base. The ability to calculate the true lifetime value of each customer is imperative forsuccess 2023, especially if a recession is in the cards – you cannot afford to waste time with low-value relationships. Stay tuned for my next post, which will focus on pricing as a key driver of both customer experience and margin optimization with your most important customers.